Treatise of Zera Yacob, Chapter IX

November 16, 2012 § 3 Comments

I know that God answers our prayers in another way, if we pray to him with our whole hearts, with love, faith and patience: during my childhood I was a sinner for many years, I neither thought of the work of God nor prayed to him; I made many sinful acts that rational nature forbids; because of my sins I fell into a trap from which man cannot free himself [by himself;] I began to be despondent and the terror of death overcame me. At that time I turned to God and I began to pray to him that he free me, for he knows all the ways of salvation. I said to God: “I repudiate my sin and I search for your will, O Lord, that I may accomplish it. But now forgive me my sin and free me.” I prayed for many days with all my heart; God heard me and saved me completely; I for my part praised him and wholeheartedly turned to him. And I said Psalm CXIV [116:1]: “I love! For God listens to my entreaty.” I thought that this psalm was written for me. I then said: “No, I shall not die, I shall live to recite the deeds of God.”

There are people who constantly accused me in the presence of the king and said: “This man is your enemy, and the enemy of the Frang;” and I knew that the king’s wrath was inflamed against me. One day the king’s messenger came to me, and said: “Come quickly to me; thus spoke the king.” I was very much frightened, but I could not flee, because the king’s men were guarding me. I prayed the whole night with a grieved heart; in the morning I rose and went up to the king. But God had made his heart soft, he received me well and mentioned nothing of the things I was afraid of. He only questioned me on many points concerning the doctrine and the [sacred] Books and he said to me: “You are a learned man, you should love the Frang, because they are very learned.” I answered: “Yes, they truly are;” for I was afraid and the Frang are really learned. After this the king gave me five measures of gold, and sent me away peacefully. After leaving [the king,] as I was still marvelling [at my fate,] I thanked God who had treated me so well. When Walda Yohannes accused me, I ran away, but I did not pray as before that [God] rescue me from the peril, because I was able to flee; man ought to do everything possible without tempting God needlessly. Now I praise Him; because I fled and am now living in a cave, I find ample opportunity to turn myself wholly to my creator; I am able to think of those things which eluded me previously and to know the truth that gives great joy to my soul. And I say to God: “I deserved the affliction which made me know your judgement.” I have learnt more while living alone in a cave than when I was living with scholars. What I wrote in this book is very little; but in my cave I have meditated on many other such things. I praise God for the wisdom he gave me and the knowledge of the mysteries of creation; my soul is drawn by him and despises everything except the meditation of God’s work and of his wisdom.

Everyday I recited the Psalter of David with a heart dilated [with joy;] and this prayer helps me considerably and raises my thoughts to God. And when in the Psalter of David I encounter things that do not agree with my thought, I interpret them and I try to make them agree with my science and all is well. While praying in this manner, my trust in God grew stronger. And I said: “God, hear my prayer, do not hide from my petition. Save me from the violence of men. For your part, Lord, do not withhold your kindness from me! May your love and faithfulness constantly preserve me. I invoke you, O Lord; do not let me be disgraced. So I shall always sing of your name, that day after day you will fulfil my desire. Turn to me and pity me. Give me your strength, your saving help, to me your servant, this son of a pious mother, give me one proof of your goodness. For the sake of your name, guide me, lead me! Rescue me from my persecutors, for the goodness you show me. Let dawn bring proof of your love, for one who relies on you. Protect me and lead me into the land, do not let me fall into the hands of my enemies. Let me hear [your] joy and exultation; do take away my hope. Counter their curses with your blessing, and let them know that you have done it.” I was praying day and night with all my heart this and other similar prayers.

COMMENT

This chapter is more autobiography and testimony than philosophy, but I have a few remarks nevertheless.

The first paragraph, in which Zera Yacob says that sin can bind us so that we can no longer free ourselves from its influence, and that we then require God’s intervention, and that God did so intervene in his life, is reminiscent of Augustine’s account of his conversion in Book VIII of the Confessions:

For the law of sin is the violence of custom [i.e. habituation], whereby the mind is drawn and holden, even against its will; but deservedly, for that it willingly fell into it. Who then should deliver me thus wretched from the body of this death, but Thy grace only, through Jesus Christ our Lord? (VIII.v.12)

…

I cast myself down I know not how, under a certain fig-tree, giving full vent to my tears; and the floods of mine eyes gushed out an acceptable sacrifice to Thee. And, not indeed in these words, yet to this purpose,

spake I much unto Thee: and Thou, O Lord, how long? how long, Lord, wilt Thou be angry for ever? Remember not our former iniquities, for I felt that I was held by them. I sent up these sorrowful words: How long, how long, “to-morrow, and tomorrow?” Why not now? why not is there this hour an end to my uncleanness?So was I speaking and weeping in the most bitter contrition of my heart, when, lo! I heard from a neighbouring house a voice, as of boy or girl, I know not, chanting, and oft repeating, “Take up and read; Take up and read. ” Instantly, my countenance altered, I began to think most intently whether children were wont in any kind of play to sing such words: nor could I remember ever to have heard the like. So checking the torrent of my tears, I arose; interpreting it to be no other than a command from God to open the book, and read the first chapter I should find. For I had heard of Antony, that coming in during the reading of the Gospel, he received the admonition, as if what was being read was spoken to him: Go, sell all that thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven, and come and follow me: and by such oracle he was forthwith converted unto Thee. Eagerly then I returned to the place where Alypius was sitting; for there had I laid the volume of the Apostle when I arose thence. I seized, opened, and in silence read that section on which my eyes first fell: Not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and wantonness, not in strife and envying; but put ye on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make not provision for the flesh, in concupiscence. No further would I read; nor needed I: for instantly at the end of this sentence, by a light as it were of serenity infused into my heart, all the darkness of doubt vanished away. (VIII.xii.28–29)

“What I wrote in this book is very little; but in my cave I have meditated on many other such things.” I always this this passage is so tragic—if only Zera Yacob had written more!

The final paragraph contains a whole series of quotations or paraphrases from the Psalms: 55:1; 40:11; 31:17; 61:8; 86:16–17; 31:4; 142:6–7; 143:8; 109:27–8. Looking at the sources, I’m reminded of Paul’s manner of quoting in his letters: the quotes are not exact, and are drawn from various places and then joined or fused together. In other words, Zera Yacob, like Paul, is drawing at will on his profound knowledge of scripture rather than looking things up. (But I should say that it’s hard for me to judge the accuracy of Zera Yacob’s quotations very well, since some of the apparent discrepancies may have to do with translation or variations in manuscripts.)

It is particularly clear in this chapter that, although he is not a Christian, Zera Yacob is a devout man.

Back to chapter VIII; forward to chapter X.

Treatise of Zera Yacob, Chapter VIII

November 10, 2012 § Leave a comment

The will of God is known by this short statement from our reason that tells us: Worship God your creator and love all men as yourself. Moreover our reason says: Do not do unto others that which you do not like to be done to you, but do unto others as you would like others to do unto you. The decalogue of the Pentateuch expresses the will of the creator excepting [the precept] about the observance of the Sabbath, for our reason says nothing of the observance of the Sabbath. But the prohibitions of killing, stealing, lying, adultery: our reason teaches us these and similar ones. Likewise the six precepts of the Gospel are the will of the creator. For indeed we desire that men show mercy to us; it therefore is fitting that we ourselves show the [same] mercy to the others, as much as it is within our power. It is the will of God that we keep our life and existence in this world. It is by the will of the creator that we come into and remain in this Life, and it is not right for us to leave it against his holy will. The creator himself wills that we adorn our life with science and work; for such an end did he give us reason and power. Manual labour comes from the will of God because without it the necessities of our life cannot be fulfilled. Likewise marriage of one man with one woman and education of children.

Moreover there are many other things which agree with our reason and are necessary for our life or for the existence of mankind. We ought to observe them, because such is the will of our creator, and we ought to know that God does not create us perfect but creates us with such a reason as to know that we are to strive for perfection as long as we live in this world, and to be worthy for the reward that our creator has prepared for us in his wisdom. It was possible for God to have created us perfect and to make us enjoy beatitude on earth; but he did not will to create us in this way; instead he created us with the capacity of striving for perfection, and placed us in the midst of the trials of this world so that we may become perfect and deserve the reward that our creator will give us after our death; as long as we live in this world we ought to praise our creator and fulfil his will and be patient until he draws us unto him, and beg from his mercy that he will lessen our period of hardship and forgive our sins and faults which we committed through ignorance; and enable us to know the laws of our creator and to keep them.

Now as to prayer, we always stand in need of it because [our] rational nature requires it. The soul endowed with intelligence that is aware that there is a God who knows all, conserves all, rules all, is drawn to him so that it prays to him and asks him to grant things good and to be freed from evil and sheltered under the hand of him who is almighty and for whom nothing is impossible, God great and sublime who sees all that is [above and] beneath him, holds all, teaches all, guides all, our Father, our creator, our Protector, the reward for our souls, merciful, kind, who knows each of our misfortunes, takes pleasure in our patience, creates us for life and not for destruction, as the wise Solomon said: “You, Lord, teach all things, because you can do all things and overlook men’s sins so that they can repent. You love all that exists, you hold nothing of what you have made in abhorrence, you are indulgent and merciful to all” [Wisdom 11:23–25]. God created us intelligent so that we may meditate on his greatness, praise him and pray to him in order to obtain the needs of our body and soul. Our reason which our creator has put in the heart of man teaches all these things to us. How can they be useless and false?

COMMENT

is “worship God your creator and love all men as yourself” really a precept of reason? Zera Yacob offered an argument for the existence of God back in chapter III. And in chapter IV he briefly addressed the further matter of worship:

He is intelligent who understands all, for he created us as intelligent from the abundance of his intelligence; and we ought to worship him, for he is the master of all things. If we pray to him, he will listen to us; for he is almighty.

And what about the Golden Rule? Jesus taught it, but I am not so sure about reason, and I would like more of an argument there. Empathy and mutual aid are natural, certainly, but so are vengeance and rivalry.

I’ve talked before about how there are lots of good rules that are not deliverances of pure reason, and I think observance of the Sabbath is another good example. Unlike murder and theft, observing the Sabbath is only required because God tells us to do it. It’s like taking out the trash as a kid—you only have to do it if your parents tell you to. Still, you do have to do it if they tell you to, and likewise we’re supposed to observe the Sabbath, not because we’re told to do so by reason, but because we’re told to do so by God. Moreover, it’s good that he told us to do that. If everyone else works seven days a week, then it’s pretty hard to take one day off yourself. But if God (or any other authority) makes everyone take a day off, then great! Everyone gets a day off.

The following is an interesting passage, because it raises a question about how Zera Yacob understands the relationship between what we should do, what reason tells us, and what God wills:

But the prohibitions of killing, stealing, lying, adultery: our reason teaches us these and similar ones. Likewise the six precepts of the Gospel are the will of the creator. For indeed we desire that men show mercy to us; it therefore is fitting that we ourselves show the [same] mercy to the others, as much as it is within our power. It is the will of God that we keep our life and existence in this world. It is by the will of the creator that we come into and remain in this Life, and it is not right for us to leave it against his holy will.

Zera Yacob evidently thinks that whatever reason reveals to be right, God wills—perhaps because reason simply reveals the will of God? In the last chapter, Zera Yacob referred to “the will of the creator revealed through the light of reason,” and see also the first sentence of the present chapter. The last sentence of this quote may suggest that, ultimately, we should do things precisely because God wills that we do them; indeed just below Zera Yacob says that “We ought to observe [things which agree with our reason], because such is the will of our creator.” As Plato observed in the Euthyphro, there must be some reason why God commands one thing rather than another, so it cannot simply be that we should do things merely because God says so. On the other hand, and as I pointed out just above, God, like a parent, can make certain things obligatory in virtue of his authority. Maybe that’s all Zera Yacob is getting at in the last line above: it is wrong to abandon the life your creator gave you in the same way that you could be said to wrong your parents by committing suicide. But on the whole it is a shame that Zera Yacob does not say more about what we would now call moral epistemology and metaethics; probably we must just accept that he has not really worked out a theory on such matters.

Regarding manual labour, we may note that in Ethiopia, as in many ancient and medieval societies, manual labour and technical trades were looked down on.

In the second paragraph, Zera Yacob offers a brief theodicy (a “justification of the ways of God to man,” in Milton’s words). God could have made us perfect, but did not do so because he wanted us to perfect ourselves and deserve our blessedness. As usual, Zera Yacob doesn’t develop the idea in detail, but in contemporary philosophy of religion, this is known as a “soul-making theodicy.”

Back to chapter VII; proceed to chapter IX.

A New Book on Zera Yacob

September 25, 2012 § Leave a comment

There’s a brand new book out on Zera Yacob: The Ethics of Zär’a Ya’eqob, by Dawit Worku Kidane. You can read the introduction on Google Books. It looks pretty interesting. As the title implies, it seems to focus on the moral philosophy. But it also seems to have some pretty substantial discussion of the historical and cultural setting. Also, it offers a brand new English translation of the Treatise (I think only of Zera Yacob’s and not Walda Heywat’s, but I’m not certain about that), which is great, since it’s only the second complete English translation of the Treatise, and Sumner’s stuff is all out of print.

If anyone has looked at this book, please let me know. If you can send me some comments, I’ll happily post them here.

In Memoriam Claude Sumner

September 10, 2012 § Leave a comment

I just discovered this obituary for Claude Sumner in SJ Africa News:

Fr Claude Sumner (AOR – GLC)

Born: 10 July 1919

Entered SJ: 14 August 1939

Ordained: 29. June 1951

Final Vows: 15 August 1955

Died: 24 June 2012Fr Claude Sumner of Eastern Africa Province (applied to French Canada) died on 24th June, 2012, in his community of Notre-Dame de Richelieu in Montreal at the age of 92 after 72 years as a Jesuit.

Fr Sumner worked for many years in Ethiopia. He taught at the University of Addis Ababa and was a pioneer in work on African Philosophy.

There would be nothing whatever on Ethiopian philosophy in English without Claude Sumner (the posts I’ve been putting up on this blog are his translations, with my own commentary added). And I’m sure a lot could be said about his influence in other languages, too.

Like myself, Claude Sumner was a Canadian who fell in love with Ethiopia. I spent a summer in Ethiopia back in 2002, and dropped by the philosophy department at Addis Ababa University in hopes of meeting him. But he was back in Vancouver, my own home town, so I missed him. I could never even find an email address for him, but I suppose I could have tracked him down if I’d really tried. Not in this life-time, now.

* * *

Update: here is a longer obituary in French.

Ethiopian Philosophy on Wikipedia

September 10, 2012 § Leave a comment

I’ve started making a small effort to improve the Wikipedia articles related to Ethiopian philosophy. Given how difficult it is to find anything online, this seems like a worthwhile enterprise. So far I’ve mainly been building up the bibliographies a bit. Perhaps others will join me?

The obvious pages already exist: Ethiopian Philosophy, Zera Yacob, Walda Heywat, Hatata, Claude Sumner. ‘Ethiopian Philosophy’ and ‘Zera Yacob’ are in the best shape, but they could all use a fair bit of work. And should there be more articles?

Treatise of Zera Yacob, Chapter VII

September 3, 2012 § Leave a comment

I said to myself: “Why does God permit liars to mislead his people?” God has indeed given reason to all and everyone so that they may know truth and falsehood, and the power to choose between the two as they will. Hence if it is truth we want, let us seek it with our reason which God has given us so that with it we may see that which is needed for us from among all the necessities of nature. We cannot, however, reach truth through the doctrine of men, for all men are liars. If on the contrary we prefer falsehood, the order of the creator and the natural law imposed on the whole of nature do not perish thereby, but we ourselves perish by our own error.

God sustains the world by his order which he himself has established and which man cannot destroy, because the order of God is stronger than the order of men. Therefore those who believe that monastic life is superior to marriage are they themselves drawn to marriage because of [the might of] the order of the creator; those who believe that fasting brings righteousness to their soul, eat when they feel hungry, and those who believe that he who has given up his goods is perfect, are drawn to seek them again on account of their usefulness, as many of our monks have done. Likewise all liars would like to break the order of nature: but it is not possible that they do not see their lie broken down. But the creator laughs at them, the Lord of creation derides them. God knows the right way to act, but the sinner is caught in the snare set by himself. Hence a monk who holds the order of marriage as impure will he caught in the snare of fornication and of other carnal sins against nature and of grave sickness. Those who despise riches will show their hypocrisy in the presence of kings and of wealthy persons in order to acquire these goods. Those who desert their relatives for the sake of God lack temporal assistance in times of difficulty and in their old age; they begin to blame God and men and to blaspheme. Likewise all those who violate the law of the creator fall into the trap made by their own hands. God permits error and evil among men because our souls in this world live in a land of temptation, in which the chosen ones of God are put to the test, as the wise Solomon said: “God has put the virtuous to the test and proved them worthy to be with him; he has tested them like gold in a furnace, and accepted them as a holocaust.” After our death, when we go back to our creator, we shall see how God made all things in justice and great wisdom and that all his ways are truthful and upright.

It is clear that our soul lives after the death of our flesh, for in this world our desire [for happiness] is not fulfilled: those in need desire to possess, those who possess desire more, and though man owned the whole world, he is not satisfied and craves for more. This inclination of our nature shows us that we are created not only for this life, but also for the coming world; there the souls which have fulfilled the will of the creator will be perpetually satisfied and will not look for other things. Without this [inclination] the nature of man would be deficient and would not obtain that of which it has the greatest need. Our soul has the power of having the concept of God and of seeing him mentally; likewise it can conceive of immortality. God did not give this power purposelessly; as he gave the power, so did he give the reality. In this world complete justice is not achieved: wicked people are in possession of the goods of this world in a satisfying degree, the humble starve; some wicked men are happy, some good men are sad, some evil men exult with joy; some righteous men weep. Therefore after our death there must needs be another life and another justice, a perfect one, in which retribution will be made to all according to their deeds, and those who have fulfilled the will of the creator revealed through the light of reason and have observed the law of their nature will be rewarded. The law of nature is obvious, because our reason clearly propounds it, if we examine it. But men do not like such inquiries; they choose to believe in the words of men rather than to investigate the will of their creator.

COMMENT

The opening of this chapter is reminiscent of Romans 1:18–25:

For the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men, who by their unrighteousness suppress the truth. For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse, for although they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him, but they became futile in their thinking, and their foolish hearts were darkened. Claiming to be wise, they became fools, and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man and birds and animals and creeping things. Therefore God gave them up in the lusts of their hearts to impurity, to the dishonouring of their bodies among themselves, because they exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator, who is blessed forever!

In my comment on chapter VI, I already talked about Zera Yacob’s optimistic view of human reason. Again he is too optimistic here. Besides the limits on our time and intellect, we are built to deceive ourselves, especially in moral matters, and the truth will often elude us despite our best efforts.

In this chapter Zera Yacob also seems overly optimistic about our natural inclinations. He argues here that our natural drives reveal the folly of ascetecism, but even non-ascetics feel temptation. Maybe it’s foolish not to marry if that is only going to lead you to use prostitutes, but married men are also tempted to stray, and that does not mean that monogamy is folly. (Well, some cynics will say that it does mean that, but Zera Yacob wouldn’t.) Life is hard, and even the upstanding face trials, as Zera Yacob himself here insists: “the chosen ones of God are put to the test.”

However, I’m perhaps being a bit unfair. Zera Yacob has already argued against asceticism and various other things in earlier chapters. So maybe in this chapter he’s just pointing to some consequences of going wrong in these areas. That would be perfectly fair.

Zera Yacob’s argument for life after death depends upon the point that life is hard, even for the just: “It is clear that our soul lives after the death of our flesh, for in this world our desire is not fulfilled.” This is a fairly famous argument now, because C. S. Lewis made it in Mere Christianity:

The longings which arise in us when we first fall in love, or first think of some foreign country, or first take up some subject that excites us, are longings which no marriage, no travel, no learning, can really satisfy. I am not now speaking of what would be ordinarily called unsuccessful marriages, or holidays, or learned careers. I am speaking of the best possible ones. There was something we grasped at, in that first moment of longing, which just fades away in the reality. I think everyone knows what I mean. The wife may be a good wife, and the hotels and scenery may have been excellent, and chemistry may be a very interesting job: but something has evaded us.

…

The Christian says, “Creatures are not born with desires unless satisfaction for those desires exists. A baby feels hunger well, there is such a thing as food. A duckling wants to swim: well, there is such a thing as water. Men feel sexual desire: well, there is such a thing as sex. If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world. If none of my earthly pleasures satisfy it, that does not prove that the universe is a fraud. Probably earthly pleasures were never meant to satisfy it, but only to arouse it, to suggest the real thing. If that is so, I must take care, on the one hand, never to despise, or be unthankful for, these earthly blessings, and on the other, never to mistake them for the something else of which they are only a kind of copy, or echo, or mirage.

But the argument isn’t a good one, at least not after Darwin. It’s very natural that we would have restless desires, because going for more is generally safer than just settling for less. The more women you sleep with, the more children you can leave behind. And so on. Also, it would be absurd to imagine that all our our desires might be satisfied after death. I’m sure the reader will be able to think of some desires of his own that he would not expect God to satisfy.

But some people do feel, with Zera Yacob, that “after our death there must needs be another life and another justice, a perfect one, in which retribution will be made to all according to their deeds.” Some people think that if there were not, then life would be absurd. For example, William Lane Craig claims that

if God does not exist and there is no immortality, then all the evil acts of men go unpunished and all the sacrifices of good men go unrewarded. But who can live with such a view?

I’m not totally unsympathetic to this, but I’m not all that impressed by it, either. For one thing, even if the fact that the evil thrive and the good suffer is a paradox of moral life, it is only one among several (the most famous is moral luck), and it is not clear to me that God or eternal life makes any difference to many of them. There just seem to be some paradoxes lurking in human thought generally, and in moral thought in particular. In fact religion can introduce new puzzles: the problem of evil is at least as difficult as the idea that there might not be perfect justice.

I’ve added further (and more sympathetic) comments on chapter VII here.

Back to chapter VI; proceed to chapter VIII.

Krause’s “Spezielle Metaphysik,” Part I

August 30, 2012 § Leave a comment

Recently I mentioned my excitement at discovering an article on Zera Yacob in an actual philosophy journal: Andrej Krause’s “Spezielle Metaphysik in der Untersuchung des Zar’a Jacob (1599–1692),” in Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie 85.3 (2003).

I’m finally getting around to reading it, and I’m going to describe and discuss it here. My German isn’t very good, so I’ll probably only go a few pages at a time.

* * *

Introduction. Krause begins by rehearsing Zera Yacob’s biography. He says that the 16th-century, Greek-derived Book of the Wise Philosophers was available to Zera Yacob in his schooling, but I assume there’s no evidence he actually read it. (I’m not familiar with the contents). Krause acknowledges that there is no reference to any philosophical texts in the Treatise.

Krause also describes the Treatise as the high point of twelve-hundred years of Ethiopian production of philosophical literature. This is only true is both ‘production’ and ‘philosophy’ are understood in a very loose sense. It is more accurate to say, as Krause does, that Zera Yacob belonged to no school and founded no school. He also says that the treatise shows a sort of intellectual affinity with modern European philsophy, though ZY presumably knew nothing of it.

Although there’s no ontology in the Treatise, Krause observes that there is a fair amount of metaphysics in the treatise, primarily in the form of rational theology (including some cosmology), but also some rational psychology. Krause’s paper will be devoted to “reconstructing and to some extent discussing the metaphysical statements and arguments of the Treatise.”

The rest of the paper is divided into two main sections: Rational Theology and Rational Psychology. The Rational Theology section contains subsections on arguments for the existence of God and God’s attributes. Next post: the first argument for God’s existence.

Treatise of Zera Yacob, Chapter VI

June 18, 2012 § Leave a comment

There is a further great inquiry, [namely:] all men are equal in the presence of God; and all are intelligent, since they are his creatures; he did not assign one people for life, another for death, one for mercy, another for judgement. Our reason teaches us that this sort of discrimination cannot exist in the sight of God, who is perfect in all his works. But Moses was sent to teach only the Jews, and David himself said: “He never does this for other nations, he never reveals his rulings to them.” Why did God reveal his law to one nation, withhold it from another? At this very time Christians say: “God’s doctrine is only found with us;” similarly with the Jews, the Mohammedans, the Indians and the others. Moreover the Christians do not agree among themselves: the Frangtell us: “God’s doctrine is not with you, but with us;” we hold the same thing, and if we would listen to men, God’s doctrine has reached only a very few people. We cannot even ascertain to which of these few it goes. Is it not possible for God to entrust his word to men whenever it pleases him? God in his wisdom has not allowed them to agree on what is false, lest it appears to them as the truth. When all people agree on one thing, that thing appears to be true; but it is not possible that all men agree on falsehood, just as by no means do they agree on their faith. I pray [you,] let us think why all men agree that there is a God, creator of all things? Because reason in all men knows that all we see was created, that no creature can be found without a creator and that the existence of a creator is the pure truth. Hence all men agree on this. When we examine the beliefs taught by men, we do not agree with them, because we find in them falsehood mixed with truth. Men quarrel among themselves; one says: “This is the truth;” another says: “No, that is false.” All of them lie when they claim to attribute to the Word of God the word of men. I kept on reflecting and said to myself: “Even if the faith of men does not come from God, it is however necessary for them and produces good effects, since it deters the wicked from doing evil and comforts the good in their patience.” To me such a faith is like a wife who gives birth to an illegitimate child, without the knowledge of the husband; the husband rejoices taking the child for his son, and loves the mother; were he to discover that she bore him an illegitimate child, he would be sad and would send her out with her child. Likewise, when I found out that my faith was adulterous or false, I became sad on account of it and of the children that were born from this adultery, namely: hatred, persecution, torture, bondage, death, seeing that these had forced me to take refuge in this cave.

However, to say the truth, the Christian faith as it was founded in the days of the Gospel was not evil, since it invites all men to love one another and to practice mercy towards all. But today my countrymen have set aside the love recommended by the Gospel and turned away towards hatred, violence, the poison of snakes; they have pulled their faith to pieces down to its very foundation; they teach things that are vain; they do things that are evil, so that they are falsely called Christians.

COMMENT

Zera Yacob claims that “it is not possible that all men agree on falsehood, just as by no means do they agree on their faith.” But this is not right. Sometimes everyone (or nearly everyone) does agree on something that is false. For example, everyone used to think that the earth was flat. Whether people all believe about something also changes over time. Thus at one point everyone thought the earth was flat, and slowly more and more people came to believe that it was round. So it is quite possible for everyone to agree on a falsehood, and also for there to be a lot of disagreement about both truths and falsehoods. Zera Yacob thinks that everyone believes in “a God, creator of all things”, and says we all agree about this because it is revealed by reason. As will be obvious to modern readers, not everyone does (nor did all people ever) believe this. Does this mean that it isn’t clear to reason after all? Well, that depends. To decide that, we would have to talk about Zera Yacob’s specific argument more (I discussed it very briefly in my comments on chapter III). But it is in fact quite possible for people to disagree even about truths of pure reason. This is because the arguments are often hard to follow (think of mathematics and logic, for example)), and anyways we aren’t very disinterested inquirers, especially when we’re arguing about matters of morality and religion. So even if Zera Yacob is wrong when he says that everyone agrees that there is a God who created all things, he could be right in his argument that there is such a God.

Now the eleven disciples went to Galilee, to the mountain to which Jesus had directed them.And when they saw him they worshiped him, but some doubted. And Jesus came and said to them, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore andmake disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age.”

But who are you, O man, to answer back to God? Will what is molded say to its molder, “Why have you made me like this?” Has the potter no right over the clay, to make out of the same lumpone vessel for honorable use and another for dishonorable use? What if God, desiring to show his wrath and to make known his power, has endured with much patience vessels of wrath prepared for destruction, in order to make known the riches of his glory for vessels of mercy, which he has prepared beforehand for glory—even us whom he has called, not from the Jews only but also from the Gentiles?As indeed he says in Hosea,

“Those who were not my people I will call ‘my people,’ and her who was not beloved I will call ‘beloved.’” “And in the very place where it was said to them, ‘You are not my people,’ there they will be called ‘sons of the living God.’”

Finally, notice that although Zera Yacob had criticized Christian moral teachings in the previous chapter, here he’s quite complimentary about Christianity in its original form. This is not too surprising, since his criticism of Christianity had mostly focussed on fasting and monasticism, which are fairly peripheral features of Christianity, and arguably are largely cultural accretions rather than reflections of basic tenets.

Back to chapter V; proceed to chapter VII.

Treatise of Zera Yacob, Chapter V

June 11, 2012 § Leave a comment

To the person who seeks it, truth is immediately revealed. Indeed he who investigates with the pure intelligence set by the creator in the heart of each man and scrutinizes the order and laws of creation, will discover the truth.

Moses said: “I have been sent by God to proclaim to you his will and his law;” but those who came after him added stories of miracles that they claimed had been wrought in Egypt and on Mount Sinai and attributed them to Moses. But to an inquisitive mind they do not seem to be true. For in the Books of Moses, one can find a wisdom that is shameful and that fails to agree with the wisdom of the creator or with the order and the laws of creation. Indeed by the will of the creator, and the law of nature, it has been ordained that man and woman would unite in a carnal embrace to generate children, so that human beings will not disappear from the earth. Now this mating which is willed by God in his law of creation, cannot be impure since God does not stain the work of his own hands. But Moses considered the act as evil; but our intelligence teaches us that he who says such a thing is wrong and makes his creator a liar. Again they said that the law of Christianity is from God, and miracles are brought forth to prove it. But our intelligence tells us and confirms to us with proofs that marriage springs from the law of the creator; and yet monastic law renders this wisdom of the creator ineffectual, since it prevents the generation of children and extinguishes mankind. The law of Christians which propounds the superiority of monastic life over marriage is false and cannot come from God. How can the violation of the law of the creator stand superior to his wisdom, or can man’s deliberation correct the word of God? Similarly Mohammed said: “The orders I pass to you are given to me by God;” and there was no lack of writers to record miracles proving Mohammed’s mission, and [people] believed in him. But we know that the teaching of Mohammed?) could not have come from God; those who will be born both male and female are equal in number; if we count men and Women living in an area, we find as many women as men; we do not find eight or ten women for every man; for the law of creation orders one man to marry one woman. If one man marries ten women, then nine men will be without wives. This violates the order of creation and the laws of nature and it ruins the usefulness of marriage; Mohammed, who taught in the name of God, that one man could marry many wives, is not sent from God.

These few things I examined about marriage. Similarly when I examine the remaining laws, such as the Pentateuch, the law of the Christians and the law of Islam, I find many things which disagree with the truth and the justice of our creator that our intelligence reveals to us. God indeed has illuminated the heart of man with understanding by which he can see the good and evil, recognize the licit and the illicit, distinguish truth from error, “and by your light we see the light, oh Lord!” If we use this light of our heart properly, it cannot deceive us; the purpose of this light which our creator gave us is to be saved by it, and not to be ruined [by it.] Everything that the light of our intelligence shows us comes from the source of truth; but what men say comes from the source of lies and our intelligence teaches us that all that the creator established is right. The creator in his kind wisdom has made blood to flow monthly from the womb of women. And the life of a woman requires this flow of blood in order to generate children; a woman who has no menstruation is barren and cannot have children, because she is impotent by nature. But Moses and Christians have defiled the wisdom of the creator; Moses even considers impure all the things that such a woman touches; this law of Moses impedes marriage and the entire life of a woman and it spoils the law of mutual help, prevents the bringing up of children and destroys love. Therefore this law of Moses cannot spring from him who created woman.

Moreover our intelligence tells us that we should bury our dead brothers. Their corpses are impure only if we follow the wisdom of Moses; they [are] not, however, if we follow the wisdom of our creator who made us out of dust that we may return to dust. God does not change into impurity the order he imposed on all creatures with great wisdom, but man attempts to render it impure that he may glorify the voice of falsehood. The Gospel also declares: “He who does not leave behind father, mother, wife and children is not worthy of God.” This forsaking corrupts the nature of man. God does not accept that his creature destroy itself, and our intelligence tells us that abandoning our father and our mother helpless in their old age is a great sin; the Lord is not a god that loves malice; those who desert their children are worse than the wild animals that never forsake their offspring. He who abandons his wife abandons her to adultery and thus violates the order of creation and the laws of nature. Hence what the Gospel says on this subject cannot come from God. Likewise the Mohammedans said that it is right to go and buy a man as if he were an animal. But with our intelligence we understand that this Mohammedan law cannot come from the creator of man who made us equal, like brothers, so that we call our creator our father, But Mohammed made the weaker man the possession of the stronger and equated a rational creature with irrational animals; can this depravity be attributed to God?

God does not order absurdities, nor does he say: “Eat this, do not eat this; today eat, tomorrow do not eat; do not eat meat today, eat it tomorrow,” unlike the Christians who follow the laws of fasting. Neither did God say to the Mohammedans: “Eat during the night, but do not eat during the day,” nor similar and like things. Our reason teaches us that we should eat of all things which do no harm to our health and our nature, and that we should eat each day as much as is required for our sustenance. Eating one day, fasting the next endangers health; the law of fasting reaches beyond the order of the creator who created food for the life of man and wills that we eat it and be grateful for it; it is not fitting that we abstain from his gifts to us. If there are people who argue that fasting kills the desire of the flesh, I shall answer them: The concupiscence of the flesh by which a man is attracted to a woman and a woman to a man springs from the wisdom of the creator; it is improper to do away with it; but we should act according to the well-known law that God established concerning legitimate intercourse. God did not put a purposeless concupiscence into the flesh of men and of all animals; rather he planted it in the flesh of man as a root of life in this world and a stabilizing power for each Creature in the way destined for it. In order that this concupiscence lead us not to excess, we should eat according to our needs, because overeating and drunkenness result in ill health and shoddiness in work. A man who eats according to his needs on Sunday and during the fifty days does not sin, similarly he who eats on Friday and on the days before Easter does not sin. For God created man with the same necessity for food on each day and during each month. The Jews, the Christians and the Mohammedans did not understand the work of God when they instituted the law of fasting; they lie when they say that God imposed fasting upon us and forbade us to eat; for God our creator gave us food that we support ourselves by it, not that we abstain from it.

COMMENT

“To the person who seeks it, truth is immediately revealed.” This is incredibly over-optimistic. Nevertheless the attitude is fairly characteristic of moral philosophers. When students ask “who is to say what is right and what is wrong,” philosophy professors will often say “you have to! You have to think it through for yourself!” In fact almost nobody is intelligent, knowledgeable, and dispassionate enough to simply work out the answers to moral questions for themselves with any reliability.

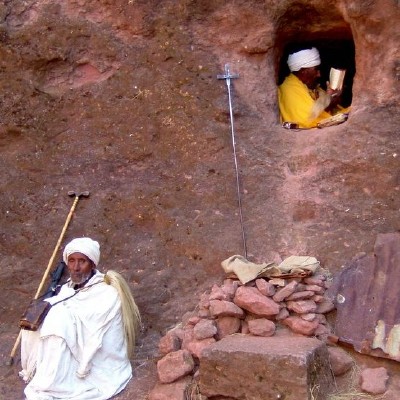

Regarding Zera Yacob’s discussion of marriage, it’s worth noting that monasticism was (and still is) very prominent in Ethiopia. (The picture at the head of this post is one I shot of a couple of monks in Lalibela in 2002.)

Marriage is an interesting case to think about in a bit more detail, because it’s really not nearly so straightforward as Zera Yacob supposes, and that shows the limits of this kind of a priori moral philosophizing. Marriage is, no doubt, suitable for human beings, and, as a matter of equity, it seems fair that each person should have one and only one spouse. But that’s hardly the end of the question. Let’s take at what Paul says about marriage in 1 Corinthians 7:25–35:

Now concerning the betrothed, I have no command from the Lord, but I give my judgment as one who by the Lord’s mercy is trustworthy. I think that in view of the present distress it is good for a person to remain as he is. Are you bound to a wife? Do not seek to be free. Are you free from a wife? Do not seek a wife. But if you do marry, you have not sinned, and if a betrothed woman marries, she has not sinned. Yet those who marry will have worldly troubles, and I would spare you that. This is what I mean, brothers: the appointed time has grown very short. From now on, let those who have wives live as though they had none, and those who mourn as though they were not mourning, and those who rejoice as though they were not rejoicing, and those who buy as though they had no goods, and those who deal with the world as though they had no dealings with it. For the present form of this world is passing away. I want you to be free from anxieties. The unmarried man is anxious about the things of the Lord, how to please the Lord. But the married man is anxious about worldly things, how to please his wife, and his interests are divided. And the unmarried or betrothed woman is anxious about the things of the Lord, how to be holy in body and spirit. But the married woman is anxious about worldly things, how to please her husband. I say this for your own benefit, not to lay any restraint upon you, but to promote good order and to secure your undivided devotion to the Lord.

Whatever the situation in Ethiopia, this isn’t terribly doctrinaire. But the key point is that Paul thinks there are special circumstances (namely the coming of Christ) that make it wise not to marry. If you don’t agree with Paul about those special circumstances, then of course you won’t see marriage his way either. The facts change things.

Polygamy is an interesting case, too (or more specifically polgyny, since polyandry is very uncommon). No doubt some men will suffer if other men monopolize multiple women. But is everyone entitled to a spouse? No doubt many women would rather be the second or third wife of a high-status man than the first wife of a low-status man. That’s unfortunate for low status men, but why should women be compelled to marry them? Well, there’s a practical reason: lots of single men with no access to women are a social hazard. This is, historically speaking, quite likely one of the reasons monogamy is in fact so widely practiced. (For an engaging discussion of such matters, see The Moral Animal by Robert Wright.) To my mind this is a better—though less obvious—justification for monogamy than Zera Yacob’s. Again, the historical and social context matters, and in un-obvious ways.

An implication: one of the reasons not to be too dismissive of the revelation in favour of one’s own `wisdom’ is that, most of the time, most of us don’t know why we do what we do, or why we should (or shouldn’t) do it.

Back to chapter IV; proceed to chapter VI.

More on Chapter VII

September 11, 2012 § Leave a comment

I was recently rereading an essay on Walda Heywat that I started some time back, and it contained a pretty nice passage (if I may say so myself) on chapter VII of Zera Yacob’s Treatise, which I posted last week. I reproduce it below.

* * *

Zera Yacob is so confident of God’s providence that it figures in a argument for life after death. It’s clear that there is another life, he says,

Moreover justice in this world is imperfect, and “therefore there must needs be another life and another justice.” The fact that Zera Yacob would argue that there must be another life on the basis of a recognition of God’s providence shows how far he is from a deep concern with evil as a philosophical problem. We see here again that “the goodness of the created thing” is a basic assumption in Zera Yacob’s thought: the insatiability of our desires is not a sign of corruptness, nor a cause for despair, nor a reason to try to extirpate them. Our natural drives are to be embraced and if there is no obvious satisfaction for them here then it must be available elsewhere.